Monday, November 29, 2010

Final Thoughts?

We spent an entire semester thinking about "religion in the South" as well as talking about the ins and outs of writing an analytical research paper. That work culminated in a 20-25 page paper! Feeling proud, right? You should. After all that writing, your final post is a freebie: give any final reflections--on your ideas about religion and the South, on the writing/research process, a post or reading about which you have more to say, etc., etc. Thanks for contributing to a successful and productive semester!

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Women and Religion

Last week, we read an essay called "Women and Southern Religion," in which the author (a little too quickly) divides camps of scholarly focus into 1) what religion does to women and 2) what religion does for women. Too facile a dichotomy, many of us agreed in class. But that said, here were the clips I mentioned (a couple of which you watched) where, even in the name of progressive gender politics, people discuss "women" in limiting ways.

First, journalist (and great-great grandson of Charles Darwin) Matthew Chapman:

Then, popular author/journalist Christopher Hitches:

Lastly, non-fiction writer on science and religion, Sam Harris:

First, journalist (and great-great grandson of Charles Darwin) Matthew Chapman:

Then, popular author/journalist Christopher Hitches:

Lastly, non-fiction writer on science and religion, Sam Harris:

Sunday, October 24, 2010

Memory and Memorials

As you probably already know, UA is in the process of renovating Foster Auditorium. In the process, the question of how exactly to go about remembering and commemorating 1963's "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door"--when then governor George Wallace attempted to keep two black students, Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood, from entering the still segregated University of Alabama.

Last year, in UA's Documenting Justice series, a team of UA students made a ten-minute short documentary about the significance of Foster and the politics of memory.

There are a lot of issues imbedded in how collectively to mark a past event, especially in a place that attaches so much meaning to something called "the past" or "tradition"...and especially when the event is charged with social change, racism, and state/federal policy.

The new design is supposed to make practical use of the space while marking the events of June 11, 1963. Do you think it does both effectively? What does it even mean to remember something "effectively" and what kinds of assumptions/appeals are made in the process? And do you think answers to such questions do/should change when the context is different...something like KA's controversial "Old South Parade"...?

Here's a picture of the new Foster design:

Click here to read about the renovation in the Crimson White

And here's the CW article after the board approved the design

Last year, in UA's Documenting Justice series, a team of UA students made a ten-minute short documentary about the significance of Foster and the politics of memory.

There are a lot of issues imbedded in how collectively to mark a past event, especially in a place that attaches so much meaning to something called "the past" or "tradition"...and especially when the event is charged with social change, racism, and state/federal policy.

The new design is supposed to make practical use of the space while marking the events of June 11, 1963. Do you think it does both effectively? What does it even mean to remember something "effectively" and what kinds of assumptions/appeals are made in the process? And do you think answers to such questions do/should change when the context is different...something like KA's controversial "Old South Parade"...?

Here's a picture of the new Foster design:

Click here to read about the renovation in the Crimson White

And here's the CW article after the board approved the design

Friday, October 15, 2010

David Bains!

This Monday, we're going to enjoy a visit from Samford Professor David Bains. After our class lets out, Prof. Bains will be giving a talk for the Religious Studies Department's Religion in Culture Lecture Series at 7:30 in Gorgas 205. That talk's title will be: "National Cathedral to National Gurdwara: Erecting American Religions in Washington, D.C.", and there will be a response given by Mark McCormick, professor of religion at Stillman. Here's the link to the facebook event page:

http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=153915967979461&ref=ts

Description of the talk he'll give that night? Well, sure, I've got that too:

Many Americans have long regarded religion as essential to the character and welfare of the nation. Accordingly, they have desired landmark houses of worship to be part of their capital city's symbolic landscape. Yet because of the religious diversity among Americans, many "national" houses of worship have been required. The erection and success of such buildings has been complicated by the separation of church and state, the congregational character of most American religions, and the bold plan and slow development of Washington. With its hegemonic claims to be a "spiritual home of the nation," Washington National Cathedral has been the most successful. Yet its claims have been continually contested by other groups. In this lecture, David Bains, an Associate Professor at Samford University, examines how these "national" houses of worship seek to shape the religious life of the United States and its capital city.

As this talk will be different from the conversation topic he'll deal with in our class, I want you to attend his evening talk and make your next post be a response to that. I'll remind you in class, send an email, etc. But with this post, maybe write a comment involving which of the 3 readings he gave us you're enjoying most/least and why... And/or, go ahead and throw out some questions you think you want to ask him or topics you want to make sure he deals with....

http://www.facebook.com/event.php?eid=153915967979461&ref=ts

Description of the talk he'll give that night? Well, sure, I've got that too:

Many Americans have long regarded religion as essential to the character and welfare of the nation. Accordingly, they have desired landmark houses of worship to be part of their capital city's symbolic landscape. Yet because of the religious diversity among Americans, many "national" houses of worship have been required. The erection and success of such buildings has been complicated by the separation of church and state, the congregational character of most American religions, and the bold plan and slow development of Washington. With its hegemonic claims to be a "spiritual home of the nation," Washington National Cathedral has been the most successful. Yet its claims have been continually contested by other groups. In this lecture, David Bains, an Associate Professor at Samford University, examines how these "national" houses of worship seek to shape the religious life of the United States and its capital city.

As this talk will be different from the conversation topic he'll deal with in our class, I want you to attend his evening talk and make your next post be a response to that. I'll remind you in class, send an email, etc. But with this post, maybe write a comment involving which of the 3 readings he gave us you're enjoying most/least and why... And/or, go ahead and throw out some questions you think you want to ask him or topics you want to make sure he deals with....

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Peer Reviews

This week, you've been spending some quality time with the work of one of your classmates. How's it going?

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Crisis and Commemoration

We had a great conversation this week about the essay by Kurt O. Berends called "Confederate Sacrifice and the 'Redemption' of the South. His claim centered around the give-and-take, push-and-pull between religious interpretation and war rhetoric. Most scholars (he identifies three different camps) discuss the effects of Christianity on the war (did it undermine the Confederacy, support it, etc.). Berends suggests, though, that there was a lot happening the other way around, too--that the rhetoric surrounding the Confederacy: patriotism, notions of a "holy war," sacrifice, etc., influenced the way that people understood their faith.

Then we meandered over to the front of the Amelia Gayle Gorgas library and looked at the commemorative rock erected outside on the quad to memorialize those soldiers from UA who fought for the Confederate forces. Here are two pictures, one I filched from google images and one I took while we stood there reading it Monday:

Then we meandered over to the front of the Amelia Gayle Gorgas library and looked at the commemorative rock erected outside on the quad to memorialize those soldiers from UA who fought for the Confederate forces. Here are two pictures, one I filched from google images and one I took while we stood there reading it Monday:

Hope you can read it... Let me know if not, and I'll type it out and post. The choices made with the language used is fascinating. I'll give you the meaty bit: "The University of Alabama gave to the Confederacy-- [this many colonels, majors, officers, etc.]. Recognizing obedience to state, they loyally and uncomplainingly met the call of duty, in numberless instances sealing their devotion by their life blood. And on April 3, 1865, the cadet corps, composed wholly of boys, went bravely forth to repel a veteran federal invading foe, of many times their number, in a vain effort to save their alma mater, from destruction by fire, which it met at the hands of the enemy on the day following"...

We talked about Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, who thought that religion should be subservient to the state... The memorial notes the "obedience to state" which was what ostensibly led the veterans to fight (loyally and uncomplainingly, no less!)--the distinction that began to be drawn between social/political/state matters and internal religious convictions is part of what allowed "the government to lay claim to citizens' ultimate allegiance and to demand the paramount sacrifice: their lives" (Berends 103). What do do with words/phrases like: "boys," "life blood," "veteran federal invading foe," "enemy," devotion," "call of duty"...?

Commemoration/Memorializing is obviously an involved process...

Thursday, September 23, 2010

David Ramsay Steele; The American South as a "Third World Country"...?

As promised, here's David Ramsay Steele suggesting that the South is "a third world country." Respond! Think especially (if it helps) in light of what you read from Beth Barton Schweiger, who discusses 18th and 19th-century revivals as highly "modern" and inventive events. The clip's about 8 minutes long, so pull out a bag of popcorn:

Sunday, September 19, 2010

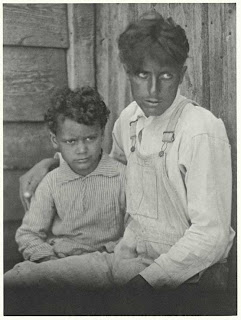

Meet the Melungeons

We've been talking about some of the ways in which we mythologize the South--the narratives privileged and excluded, the complicated notion of "a simpler time," the way nostalgia can be a reductive practice, etc. Last week, we read an essay by Jon F. Sensbach called "Before the Bible Belt: Indians, Africans, and the New Synthesis of Eighteenth-Century Southern Religious History." Sensbach calls our attention to the fact that an evangelical Protestant "Bible Belt" was not at all a foregone conclusion in the American South. He situates the South as a transatlantic space, subject to market forces, myriad cultural interactions/confrontations and migrations of German, African, Native American, and French populations, etc., etc., etc.

In our efforts to complicate "the South" and begin looking at "Souths" that explode a seemingly monolithic tent, I thought I'd introduce you to another group of Southerners you may not be familiar with: the Melungeons.

"Melungeons" refer to groups of Appalachians with African, European, and Native American ancestries.

The convergence of races and regions here offers a nice answer to why it's more than a little tricky to talk about "the South" as a singular experience. Before--and after--something called "the Bible Belt" began to emerge, there were--and are--communities that complicate that very category.

If you want to find out more:

http://www.melungeon.org/node/4

http://www.melungeons.com/articles/jan2003.htm

http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mtnties/melungeon.html

There are lots of other sites too...have some fun with Google and Wikipedia.

In our efforts to complicate "the South" and begin looking at "Souths" that explode a seemingly monolithic tent, I thought I'd introduce you to another group of Southerners you may not be familiar with: the Melungeons.

"Melungeons" refer to groups of Appalachians with African, European, and Native American ancestries.

They were identified by some as Indian, Portuguese, mulatto, Creole, black, or white. Whatever the case, they were--and still often are--called a very "mysterious" people, as their race(s) and "origins" are not easily pinned down. Most were practitioners of various stripes of Protestantism (many were Baptist). Speculations about these populations abound (we like for people and things to have easy and unchanging names, after all). This trailer, apart from bad background music, gives you a sense of all the different ideas on how these groups should be identified:

The convergence of races and regions here offers a nice answer to why it's more than a little tricky to talk about "the South" as a singular experience. Before--and after--something called "the Bible Belt" began to emerge, there were--and are--communities that complicate that very category.

If you want to find out more:

http://www.melungeon.org/node/4

http://www.melungeons.com/articles/jan2003.htm

http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~mtnties/melungeon.html

There are lots of other sites too...have some fun with Google and Wikipedia.

Crimson White on Campus History

As promised: the article from The Crimson White on campus history and the men some buildings were named for...

Find that article, called "Building Names Reflect Different Era on Campus" here:

The response suggests that "History is history--and news should be objective." In fact that's it's title. Read it here:

What do you think about the call for an "objective" view of "history?" I'm wondering about the invocation of something called "the past" (when does such a thing begin and end? at what point do we start drawing boundaries around it, etc?), and our relationship to it as people separated by time and context but with a shared region...

Wanna go visit the Gorgas rock next class?

Monday, September 13, 2010

Only the Conscious Counts?

A quick conversation starter... Several posts on your own blogs and comments to this blog's posts have brought up the issue of performance. We often rely on a distinction between "being" a certain way and "acting" a certain way...but I'm thinking that's a line that deserves some smudging.

Specifically: in comments about Trail Maids, etc., there's a running theme of what they're thinking about as they dress up, playing "dress up" in general, and whether or not they're knowingly hashing out issues of slavery. Now, the Trail Maids and the issue of "southern womanhood" is just one example...Surely this question of consciously doing this or that can translate to all sorts of topics when discussing religion and the South.

SO, since that's the case, let me add the following (to the specific case of trail maids/femininity):

1. I would be pretty surprised if someone, as she puts on an antebellum dress, actively thinks while she picks up her parasol: "I am now choosing to be complicit in a social script steeped in the horrors of slavery."

2. I'm not sure if the fact of #1 matters though... Or does it? Tell me what you think.

3. Some theory for your reading/thinking pleasure (posted a shorter version of this in a comment to the trail maids, too):

In the chapter you read from McPherson's Reconstructing Dixie, McPherson suggests:

"Central to constructions of southern femininity is a notion of masquerade or performance...In her 1929 essay 'Womanliness as a Masquerade,' [Joan] Riviere structures an equation between femininity/womanliness and masquerade, writing that 'the reader may ask how I define womanliness or where I draw the line between genuine womanliness and the masquerade...they are the same thing'. In [Mary Ann] Doane's analysis, such a formulation of femininity renders it 'in actuality non-existent' because 'it makes femininity dependent upon masculinity for its very definition'. For Doane, femininity as masquerade is both normal and...pathological. Such an understanding of normal or aberrant femininity as always a masquerade, a performance, echoes my own claim that femininity is a social and discursive construction, and thus its contours are always sketched in relation to other markers of difference. But Doane's argument that this approach makes femininity always dependent on, derivative of, masculinity...enacts an erasure of the other social relations against which femininity takes shape and is performed (21-22).

McPherson wants to add to sexual difference the differences in race and region that also mark the masquerade, so she sees herself as adding to and expanding what Doane and Riviere do in psychoanalytic contexts. Nonetheless, the central point is still one of whether or not social actors must be CONSCIOUSLY engaged in something in order to be identified as engaging in it.

There's an interesting debate to be had here, as there's surely something to be said for personal identification (I am able to mark myself or identify as this or that no matter what scholars or peers might say to the contrary). At the same time, don't social frameworks and interests get stacked up or dismantled by our often unconscious behaviors?

Personally, I don't find a lot of use for talking about things like "intent" or the "unconscious." I'm not telepathic, and I don't know what swims in the gray matter of others. I do find a lot of use in talking about behavior and action, though. And whether these things are "conscious" or not, they seem to have material consequences in a discursive and material world.

So does it matter whether we know what we're doing if we're still doing it?

123go!

Specifically: in comments about Trail Maids, etc., there's a running theme of what they're thinking about as they dress up, playing "dress up" in general, and whether or not they're knowingly hashing out issues of slavery. Now, the Trail Maids and the issue of "southern womanhood" is just one example...Surely this question of consciously doing this or that can translate to all sorts of topics when discussing religion and the South.

SO, since that's the case, let me add the following (to the specific case of trail maids/femininity):

1. I would be pretty surprised if someone, as she puts on an antebellum dress, actively thinks while she picks up her parasol: "I am now choosing to be complicit in a social script steeped in the horrors of slavery."

2. I'm not sure if the fact of #1 matters though... Or does it? Tell me what you think.

3. Some theory for your reading/thinking pleasure (posted a shorter version of this in a comment to the trail maids, too):

In the chapter you read from McPherson's Reconstructing Dixie, McPherson suggests:

"Central to constructions of southern femininity is a notion of masquerade or performance...In her 1929 essay 'Womanliness as a Masquerade,' [Joan] Riviere structures an equation between femininity/womanliness and masquerade, writing that 'the reader may ask how I define womanliness or where I draw the line between genuine womanliness and the masquerade...they are the same thing'. In [Mary Ann] Doane's analysis, such a formulation of femininity renders it 'in actuality non-existent' because 'it makes femininity dependent upon masculinity for its very definition'. For Doane, femininity as masquerade is both normal and...pathological. Such an understanding of normal or aberrant femininity as always a masquerade, a performance, echoes my own claim that femininity is a social and discursive construction, and thus its contours are always sketched in relation to other markers of difference. But Doane's argument that this approach makes femininity always dependent on, derivative of, masculinity...enacts an erasure of the other social relations against which femininity takes shape and is performed (21-22).

McPherson wants to add to sexual difference the differences in race and region that also mark the masquerade, so she sees herself as adding to and expanding what Doane and Riviere do in psychoanalytic contexts. Nonetheless, the central point is still one of whether or not social actors must be CONSCIOUSLY engaged in something in order to be identified as engaging in it.

There's an interesting debate to be had here, as there's surely something to be said for personal identification (I am able to mark myself or identify as this or that no matter what scholars or peers might say to the contrary). At the same time, don't social frameworks and interests get stacked up or dismantled by our often unconscious behaviors?

Personally, I don't find a lot of use for talking about things like "intent" or the "unconscious." I'm not telepathic, and I don't know what swims in the gray matter of others. I do find a lot of use in talking about behavior and action, though. And whether these things are "conscious" or not, they seem to have material consequences in a discursive and material world.

So does it matter whether we know what we're doing if we're still doing it?

123go!

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

The Politics of Parody

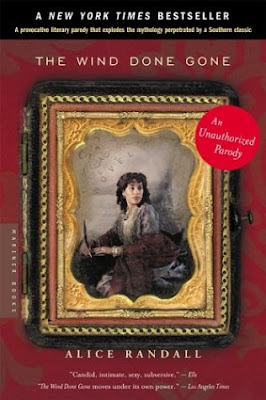

We ran out of time before I could show you this book (I'll bring it to class Monday), so I thought I'd give a quick note about it here. Alice Randall (writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt U...I think she's still there? someone correct me) wrote a novel called The Wind Done Gone, which Houghton Mifflin published in 2001.

|

| Read a review here: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HST/is_3_3/ai_75121833/ |

The book is touted on the front cover as "A provocative literary parody that explodes the mythology perpetrated by a Southern classic." It follows the story of Cynara (called Cindy), the daughter of a white plantation owner and the domestic worker we've known as Mammy. Scarlett is her half-sister, and is called "Other" throughout.

Now, such a text (it explodes a mythology perpetrated by a classic, after all) is bound to have its controversies. In fact, the estate of Margaret Mitchell (author of the "original" Gone with the Wind) sued Randall for copyright infringement. I think that's hilarious, but anyone else want to have a go with a different reaction? What it suggests is that Mitchell's "classic" epic is an untouchable tale, at least in literary venues, and that parodies/altered versions, etc., are laying claim to something unclaimable. Don't screw up Scarlett. Does this have any parallels to visions/versions of Southern nostalgia and memory in general? Or not?

Want to know how the suit finally settled? Okay, I'll tell you. The parties settled with the understanding that Houghton Mifflin would continue to print copies of the book as long as it made clear it was an "unauthorized parody" (hence the fun red stamp directly on the cover). Mitchell's estate also asked the publisher to make a donation to Morehouse College in Atlanta (an all-male historically black college), which Houghton Mifflin did. The book's publication/distribution was halted for a month when the suit was filed. Both parties reserve their rights with future reproductions of the book...

Reviews of the book describe it as fiercely controversial and entirely wonderful. I'm not sure it's either. Nonetheless, it hit a nerve in regards to its play, its parody of something seemingly "classic" about the South. What sorts of things does that fact suggest?

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Mythologizing the "Southern Lady"

Poor Scarlett. That silly war ruins all the best parties:

Our readings this week talk about how we codify and memorialize something called "Southern identity." *Gone with the Wind* is a perfect example of the nostalgic vision of a South that seems totally removed from the very infrastructure upon which it relied.

Here's an example from the film, where romance and religious ritual are bound up with racial subjugation and economic disparity:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oorFyVS23ns&feature=related

In Tara McPherson's Intro to *Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South*, she talks early on about the myth of the "Southern Lady": "[The South] remains at once the site of the trauma of slavery and also the mythic location of a vast nostalgia industry. In many ways, Americans can't seem to get enough of the horrors of slavery, and yet we remain unable to connect this past to the romanticized history of the plantation, unable or unwilling to process the emotional registers still echoing from the eras of slavery and Jim Crow. The brutalities of those periods remain dissociated from our representations of the material site of those atrocities, the plantation home. Furthermore, the very figure who underwrote the widespread lynching of black southern men (and women) during the era of segregation in the South somehow remains collectible. The white southern lady--as mythologized image of innocence and purity--floats free from the violence for which she was the cover story..."

The romanticized version of something called Southern femininity relies on a firmly entrenched structure of economic access and race-based labor framework. Interestingly, Mammy becomes the voice of maternalistic morality, telling Scarlett to "behave" and to "act like a lady"...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G4546UkGWSw&feature=related

We talked about this a little in class, but what do you make of Alabama's Azalea Trail Maids?

Here's a blurb about the controversy that ensued after their being asked to march in Obama's inaugural parade:

http://www.local15tv.com/news/local/story/Controversy-Over-The-Azalea-Trail-Maids/_log9pDFgk-nF4cuv1wq3Q.cspx

The father of one of the maids says in the article: "they've never represented slavery or racism.... only

More? Okay, sure:

http://www.wsfa.com/Global/story.asp?S=9655036

So are these innocuous images based on popular culture's trips to the movies? Should there be any responsibility attached to these representations? What does this suggest about the politics of memory and memorializing?

Sunday, August 22, 2010

True Blood...True South?

U.S. pop culture (especially angsty teens) loves vampires again. Not creepy "classical" sorts in the vein (pun intended) of Count Dracula and dank mansions. Now instead of Counts, we've got Confederate Soldiers. And instead of mansions, we've got bars and antebellum homes. Well, at least in "True Blood." The series is particularly interesting in its presentation of the South (takes place in Louisiana bayou country) vis-a-vis the presence of supernatural..."forces"? Religion gets a not-so-subtle treatment in the show, especially in regard to us/them and good/evil social dichotomies. But in a Southern context, this plays out in all sorts of (interesting? troubling? compelling? ridiculous?) ways.

Since we can't spend a semester just on this one show (dry those eyes), just take a look-see at the opening credits:

Telling images, no? There's an especially remarkable triangulation of space/setting, religious rituals, and sexuality. We see a very specific South: one of marshes, old homes, abandoned cars, bars made of splintered boards, racial hatred and violence. The religious overtones are pretty specific too: crosses, charismatic church services, prayers, baptism. And then, lots and lots of sex. Noticeably absent? Vampires. Not even vampire lore or archetypes. Loads of jumping and writhing though (alongside a decomposing animal or two or three or five), and that ends up standing in for our more traditional images of the creepy sensuality that accompanies so many vampire narratives. The juxtaposition of bodies in religious and sexual contexts is something that comes up again and again in the show itself. And the stereotypes are pretty easy to identify. So what do we make of the huge success and popularity of "True Blood"? Marketing magic? Just one more piece of the vampire craze? Or is there anything to be said for the ways in which we understand religion alongside physicality in the South? And if so, what might be said about it?

Since we can't spend a semester just on this one show (dry those eyes), just take a look-see at the opening credits:

Telling images, no? There's an especially remarkable triangulation of space/setting, religious rituals, and sexuality. We see a very specific South: one of marshes, old homes, abandoned cars, bars made of splintered boards, racial hatred and violence. The religious overtones are pretty specific too: crosses, charismatic church services, prayers, baptism. And then, lots and lots of sex. Noticeably absent? Vampires. Not even vampire lore or archetypes. Loads of jumping and writhing though (alongside a decomposing animal or two or three or five), and that ends up standing in for our more traditional images of the creepy sensuality that accompanies so many vampire narratives. The juxtaposition of bodies in religious and sexual contexts is something that comes up again and again in the show itself. And the stereotypes are pretty easy to identify. So what do we make of the huge success and popularity of "True Blood"? Marketing magic? Just one more piece of the vampire craze? Or is there anything to be said for the ways in which we understand religion alongside physicality in the South? And if so, what might be said about it?

Monday, August 16, 2010

What Religion in the South Looks Like (?)

So if Scarlette O'Harlette and fried chicken (along with some maps, which, we'll certainly talk about--those aren't so innocuous either!) are the images that show up for a search of "southern," what happens when something called "religion" gets thrown into the mix? Well, I'm glad you asked:

Hmm, so now we've got tiny churches, a lynching, the book "Baptized in Blood," and Jerry Falwell (among other things). This offers a pretty specific brand of Protestantism to partner with images of the South. Fair? Unfair? Falwellian? (no, I'm not sure what that means)

Hmm, so now we've got tiny churches, a lynching, the book "Baptized in Blood," and Jerry Falwell (among other things). This offers a pretty specific brand of Protestantism to partner with images of the South. Fair? Unfair? Falwellian? (no, I'm not sure what that means)

Seeing the South

Depending on who you are and where you've lived, you may have very specific ideas about where "the South" is, what it's like, and what role something called "religion" plays there. People debate whether states like Texas or Florida "count" as the South, whether the region should include the Caribbean, what it means to be "Southern," etc. More specifically, if we play a little visual free association, different images might come to mind if someone asks you to think about the South...(like? what say you?). So, how we see the American South will vary, of course, but I thought it might be telling to look at what a huge search engine like Google had to say about the matter. If you search "Southern" in Google Images, here's a snapshot of the first images that pop up:

These images seem to offer a pretty particular vision of what "southern-ness" is all about...And if that's the case, what (if anything?) should be read into the fact that the most popular/recognizable images of what's "Southern" are things like knife-laden Confederate flags surrounding a buxom blonde wearing ripped jeans (next to a "Southern belle" in corset and big skirts), fried chicken, and one "Scarlett O'Harlette"?

In other words, do you think there's a tension between the South that we live in and the South that appears in a larger cultural imagination? Or not? Where do these images come from?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)